1. Perch drawing

We gathered for a group meeting to look at the drawings. Asking the right questions was essential.

What do you notice in a drawing that reminds you of exactly how the fish looked?

What details did someone include that are very important?

Is there something in someone else's drawing that you wish you had included in your own?

2. Squid Drawing

3. Underwater Collage

4. Bulletin Board

At this point, I prepared a bulletin board for parents, colleagues and other students. Our class took a field trip? to the space just outside our classroom to see what other people would be seeing of the children's work. I shared some thoughts about how they had been helping each other to work, and they asked me to read aloud every bit of text. Each child was represented by one picture. Along with being pleased to see their work displayed, they saw the connections from one piece to another.

They began to understand each discreet effort as a piece of developing a larger body of community work, their individual contributions as part of a larger whole.Emily: How did Evelyn make the octopus?

Evelyn: I drew it then I cut it out, and I glued it on the side where the pencil was so you don't see the pencil.

Ms. Tonachel: When Myasia used a pencil and then cut it out, she decided that she wanted the pencil lines to show. I see pencil lines on lots of pictures. Evelyn thought, if I flip it over, the pencil lines won't show.

Myasia: And that's what I did! Cause there were pencil lines on there, so actually when I was not listening, I put it on the wrong side and that looks like I didn't draw any lines.

Juliette: How did Myasia make the seaweed?

Myasia: This one, I only cutted it out, and then the other one, I only used a pencil then I cut it out.

Ebony: I want to know how Myasia made that long, skinny shape.

Myasia: I made it because I wanted an eel. First, I drew the picture on the paper, the white piece of paper, then I cut it out.

Ms. Tonachel: So, Evelyn just used scissors, and Myasia used a pencil first and then used scissors.

Myasia: Yeah.

Emily: I wonder how Alison made that clownfish.

Alison: How I made the clownfish? The clownfish that I made was that I cut out the orange fish out of orange paper and then I cut out some white stripes, and then I glued the white stripes onto the orange fish, then I glued the orange fish onto the paper. And then I decided to make the bubbles another day, that were light blue.

Winston: Or another way you could do it is you could cut the face, cut that [section], cut that [section], and then you could leave them so white paper could?you could use the white paper as the white stripes.

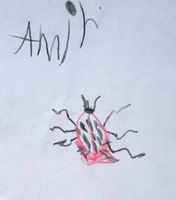

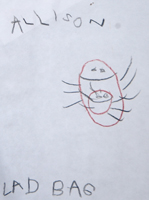

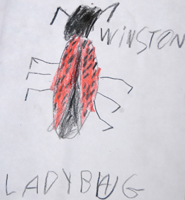

5. Ladybugs

One group's conversation follows:

Ms. Tonachel: Let's look at one picture at a time. The artist will talk first and then other people can say what they think. Is there anything you'd like to change about your drawing to make it look even more like a real ladybug?

Amir: I want to put some red in the place where the dots are and then put a black line in the middle.

Allison: Make the legs straight.

Amir: I made it that way because I noticed the legs have a lot of joints and the antennas.

Winston: Make the dots more darker.

Amir: I saw one of them had lighter dots.

Allison: [I would change] nothing.

Amir: A black line in the middle.

Alison K.: Maybe you could color the head black because look at these the head is black.

Allison: Okay.

Evelyn: Maybe you should add some antennas so it would look more like a real ladybug because the real ladybugs had them.

Allison: Okay.

Winston: I got all the details.

Alison K.: These [real ones] look really round and yours looks skinny, so maybe change it to round.

Allison: Maybe color the tips clear.

Winston: I can't color it clear.

Allison: Maybe keep it a little bit white.

Winston: Maybe the antennas should go straight up.

Evelyn: I thought I should put some white over it to try to make new ones because they look kind of lopsided.

Allison: I think you should do the same thing.

Amir: On the antennas I think you shouldn't put any dots.

Winston: I think you should put a little wing.

Evelyn: I didn't want to, like you didn't want to.

Alison K.: I could change it to erase these antennas because I can't really see them. The reason why one is all black is because it's the bottom, the backside.

Amir: You should connect those two legs.

Alison K.: I don't want to take that advice because I couldn't really see them.

6. Reflections About Critique

What shared language emerges?

I was inspired by...

I notice...

Another way you could do it is...

I wonder...

Maybe...

How did you...

What if...

What habits began to form?

Asking for advice

Sharing observations

Sharing ideas

Copying is acceptable

Referencing past experiences

Some further thoughts about critique

Critique gives both the artist (writer, block builder, mathematician) and the observer something else to go on, a suggestion for a new turn in thinking and action.

If we are successful at changing the lens of comparison, subjectivity, and favoritism through new language and attitudes, and if we make clear that every child's every effort has value towards learning, then children are encouraged to develop a habit of expansiveness in their thinking.

The idea that "copying" is being inspired by someone else's work is a positive learning tool can be an uncomfortable one. Parents, too, in looking at their children's products, need to know that in a culture of collaboration, the sharing ideas, working from each other's beginnings, and offering suggestions, are welcome parts of any individual's learning. We can all ask children, "Where did that idea come from?" and "How did you learn to do that?" thereby encouraging children to reference their own past experiences and the contributions of others to their own thinking and discovery.

When children are engaged in looking carefully at each other's work, their ideas expand. They regard other people's work as resource, and so discover new paths of thought to pursue, new techniques and strategies to try. They enter another realm of imagination; that is, through the ideas of others and through the very effort of expressing their ideas about another's work they imagine and explore unfamiliar ways of expressing themselves.