In the atelier, three to five year-old boys, Emiliano, Simone, and Giacomo, are sitting around a big table with various shapes and sizes of white paper and drawing materials. Their task is to work together to draw a city. Before they begin, the teacher asks the children if they want to listen to their previous conversations and revisit the drawings they had made individually a few days before. The boys agree.

Documentation Examples > Examples of documentation that is shared more widely

The City of Reggio

School: Municipality of Reggio Emilia

2. The Boys' City

After a brief discussion, the three boys decide to choose the largest piece of paper on the table.

Emiliano: To make a city that's really big you need a big piece of paper!

Simone: As big as the earth-as big as a city.

Emiliano and Simone begin to draw, while Giacomo places himself at the side of the piece of paper.

Conversation among the boys is almost absent at the beginning; it seems that the initial agreement (about where to start in drawing their city) has been enough to enable them to proceed. While Emiliano and Simone sit close together and begin to draw the central square of the city, Giacomo, sitting beside the paper with his elbows on the table and his chin resting on his hands, seems for now to have decided just to observe what happens. In this first phase, the verbal language that accompanies Emiliano and Simone's graphic representation focuses on the essential.

Emiliano: All cities start from a square that's in the middle of the city.

Simone: Okay, we' leave space at the bottom to make the street, that way people can leave and go out.

Giacomo still seems not to participate in the group. For the moment, the teacher decides not to urge him to take part; perhaps it is better to wait for him or for the situation to make the decision instead. Emiliano and Simone, meanwhile, are drawing very close together-their hands overlap, they switch seats often -while the curves of the street they are drawing steadily approach Giacomo. Perhaps it is an initial invitation to their friend to take part in the project.

Simone: The streets go to so many places, and there's one square after another in the city.

Emiliano: Yeah, otherwise you'd get lost. We'll make it with some curves that go that way. Toward where Giacomo is.

After about twenty minutes, Simone explicitly invites Giacomo to participate.

Simone: Giacomo, why aren't you doing anything?

His friend's request makes Giacomo slightly uncomfortable, and after this call to participate he replies.

Giacomo: Cities have to work, and I have to see if it works.

Emiliano: See, Giacomo, this is a different square, it's the one with the field where the children play, and all the houses are different.

This explanation by Emiliano gives Giacomo the possibility of entering into a relationship with the other two children by way of an offer of competence.

Emiliano: Giacomo, can you draw the roofs of the houses? Come on, try!

Giacomo: I know how to make houses with round roofs.

Simone: Will you help us then?

Giacomo: Okay!

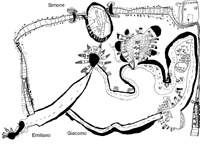

More than thirty minutes have passed since the work began, and in this phase the project becomes more clearly defined. The repetition of certain models (the square) facilitates the children's shared planning and executing. Now it is Giacomo who makes proposals.

Giacomo: Let's make another square. I'm sure there are lots of squares in the city.

Simone: Should we make one with a soccer player who's practicing?

Giacomo: Yeah, good idea!

The three boys are now working side by side, with Simone occupying the central position in the group and engaging his companions in discussion.

Just when the whole group has formed, however, it divides again. Emiliano, realizing that all three boys are working in a restricted space, decides to move to the other side of the paper to make the sidewalks.

Now Simone and Giacomo form a new pair. The square that is represented also becomes a resting point, a place of conversation, a stimulus for the boys' verbal and graphic development. It seems clear that the streets that are drawn become connections between one square and another, a kind of backbone that progressively traces the outlines of the city as it grows. The city that is developing seems to be defined by the functions carried out inside it.

Giacomo: In the squares there are people talking.

Simone: There are pretty squares and ugly ones. Then there are also some squares for parked cars and for soccer players.

Emiliano: I think cities that don't have squares are kind of strange.

Giacomo: I think they don't work well because the people don't know where to be.

Simone: Cities are all connected by the streets and the railroads, right, Giacomo?

Giacomo: Well, yeah, the streets are important for keeping the city together and for making it work.

Giacomo connects another street to Emiliano's street, while Simone adds the railroad and the playground. The first elements of autobiographical narration emerge.

Simone: In the afternoon I go to play at Campo di Marte park.

Each boy now focuses on his own ideas and the verbal interaction of the group is suspended. Simone's railroad, Giacomo's streets that lead to the center of town, and Emiliano's small squares that are being added to the map provide new connections and new complexities. As a group, the boys produce their own idea of a city and progressively define the objectives they want to reach together. The ultimate goal is to make an interconnected city: it must be possible to find a path through the whole city, and each boy steadfastly pursues this mission.

At this point, their city appears to be such a complex urban web that a pause is needed to check the new connections.

Emiliano: We need to see if it's all connected.

Simone: Like in real cities.

Giacomo: We need to make sure that the whole city is connected and that nobody gets lost.

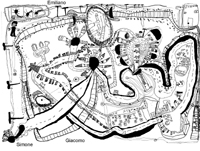

The children think about how to verify this and finally agree to go over the streets with their fingers. The test will be carried out by each member of the group, a rule of fairness on which everyone agrees. Emiliano, after having traveled through the city and its connections, gives a new impetus to the work by asking a question.

Emiliano: Hey guys, but how can you live in this city at night? We don't have any light for the streets, we don't have electricity!

This re-launching of the project generates new ideas and requires that new roles be taken on in the group.

When their work is finished and the children revisit the map with the teacher, they assess not only the aesthetic result of their representation, but also the consistency between the ideas expressed in the group as they worked and the final map of the city.

Giacomo: We made a beautiful city even though it's a little bit messy.

Emiliano: All the streets take you somewhere. It's a city where you can't get lost, where you're not afraid.

Simone: It's a city that could be Reggio Emilia, because there's the Campo di Marte, but it isn't Reggio. Maybe it's called City of the World, because all the people in the world can live in this city.

The city represented by Emiliano, Simone, and Giacomo is one full of functions and connections. The train station, the bus station, the aqueduct, the sewers, and the electrical system are not simply topological landmarks but are important elements for the real functioning of a city, essential to the life of the people.