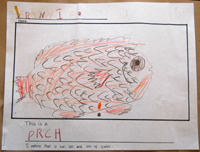

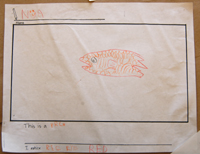

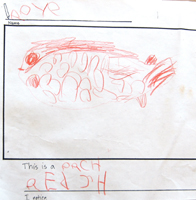

1. Perch drawing

As part of our study of ocean life, each child made an observational, or scientific, drawing of an ocean perch given to us by Mr. Wulf, the local fish monger. I noticed in working with small groups that even though the children had developed a good vocabulary of fish body parts, they needed many reminders to look at the fish. I continuously pointed out details to include in their drawings. In fact, some children approached the table with the fish on it and immediately began drawing from their previous knowledge base and imaginations, not even looking at the fish. Although the drawings they produced looked impressive to colleagues, I knew that I wanted them to be able to do this more successfully without me pushing them along at every pencil mark.

I had a hunch that with practice the children could help each other. In fact, I anticipated that the children could be much more effective in prompting one another than I could in my attempts to prompt each student. It would require of me guiding their observations and their comments toward collaboration, not competitive comparison, so that they could build a habit of positive critique. I did not want to hear them say, "I like this drawing." I wanted them to develop a shared vocabulary that would help them provoke each other toward more satisfying representational experiences.

We gathered for a group meeting to look at the drawings. Asking the right questions was essential.

What do you notice in a drawing that reminds you of exactly how the fish looked?

What details did someone include that are very important?

Is there something in someone else's drawing that you wish you had included in your own?

The conversation was lively, highly respectful and productive. Children spoke carefully to describe various aspects of the fish drawings and how they related to what they remembered the real fish to look like. Not having a photograph of the fish there, children were not comparing drawings to the real thing, but were using the drawings to bring the fish forward in their minds; they used each other's documentation to revisit the experience of studying the fish. As one child remembered, "It was hard to draw with this hand because I was holding my nose with this one." This exercise made their efforts more relevant: drawing a fish wasn't just a task the teacher required; it moved the children toward exciting new understandings.